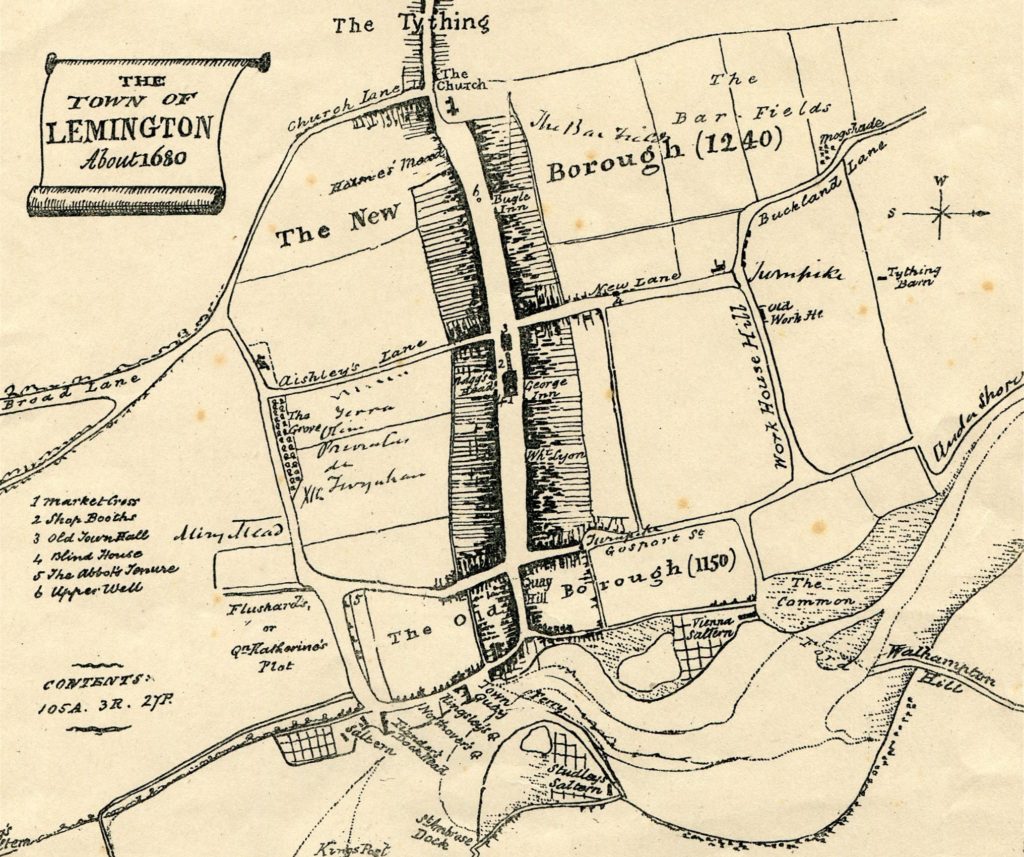

Lymington’s future as a port and economic centre for the south of the New Forest was established around 1200 when it was granted a charter by William de Redvers, the lord of the manor. In return for an annual fee and property rents the new burgesses of Lymington were exempted from paying tolls and customs duties anywhere on de Redvers lands. This provided commercial advantages for their business and trading interests and encouraged people to settle in the new town.

Perhaps most importantly the charter laid out a new borough centred on a long straight street – the High Street. This was lined with long, narrow burgage plots each 5 ½ yards wide, a measurement still found among the shopfronts at the bottom of the hill. The houses were set right on to the street and the end of their plots backed on to fields. Here the burgesses could live and set up businesses to sell and trade goods in return for an annual rent of sixpence.

The Medieval High Street

The High Street’s medieval houses were mostly timber-framed with plastered wattle and daub panels. Although designs changed over time, these were the usual materials until the late 17th century.

Some buildings were roofed with thatch, others with tiles or slate. The gardens provided space for growing fruit and vegetables, stables, wells for water and cess pits for waste. With the weekly markets, the movements of livestock and no sewerage system, the medieval High Street would have been a dirty and smelly place.

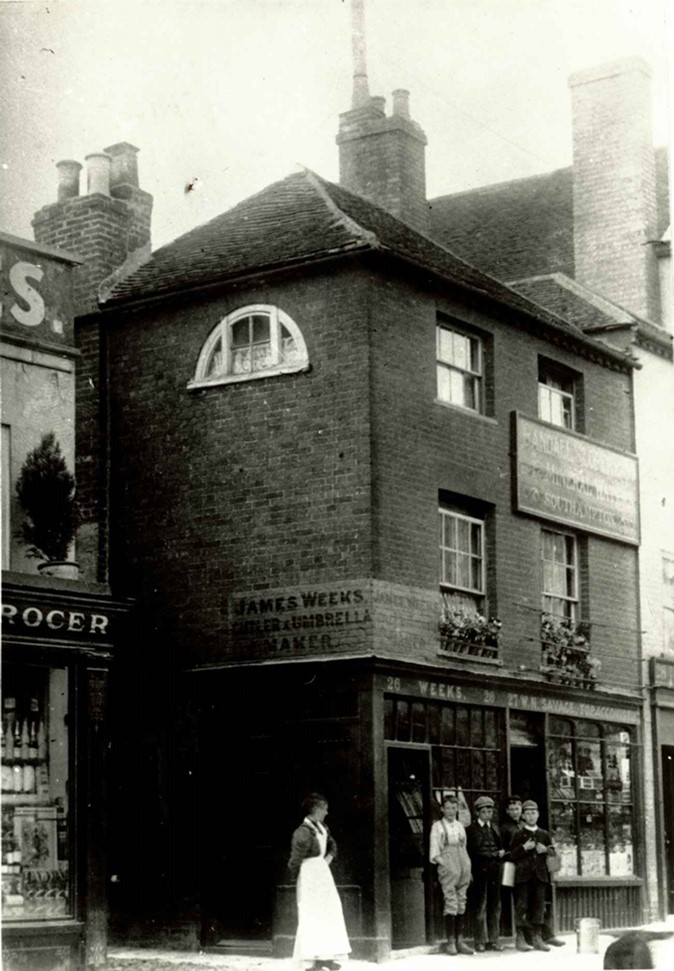

Evidence of the High Street’s medieval origins survive in several properties. This, combined with the lack of records, is the key reason local historians such as Jude James refute claims that Lymington was burned by the French. At Osbornes (Nos 26-27) the front is Georgian but inside are the remains of a medieval timber-framed building from around 1480-1500. Plastered wattle and daub panels can be seen on the right hand wall and just inside, above the shop window, are the wooden beams of a jetty (projecting beams that allowed the first floor to overhang the street and provide more space inside). Jettied frontages like this can be seen in surviving medieval buildings in places like Winchester, York and Canterbury.